The history of agricultural mechanization is closely linked to that of the tractor. However, the tractor was the result of an evolution that began in the very early 1700s when steam engines began to spread, units which for the industrialization of the Western World can be considered akin to the “Big Bang” that gave rise to the Universe.

The first agricultural tractors produced in limited series appeared in the United States in 1892 but were called “gasoline traction engines” or “traction engines.” A few years later, at the beginning of the last century, other self-propelled agricultural machines appeared, almost always oriented towards land cultivation, but they too were not called tractors but by various appellations. “Auto plow,” “motor plow,” “plow,” “automobile plow,” “agricultural automobile,” and others. To see the term “tractor” officially recognized, one had to wait until 1906 when, according to various testimonies, the sales director of the American company Hart Parr, the first to mass-produce such machines, baptized his machines as such. From “tractor” to “trattore” in Italian, the step was obviously short, although initially, and until the end of the First World War, the feminine term “trattrice” was popular, still used today in many technical and educational texts but now abandoned in common usage in favor of the masculine appellation, more suitable for a machine destined to exhibit increasingly important efforts in the field.

Agriculture before the tractor: The steam engine

The above allows us to affirm that agricuttural mechanization did not start with the development of the first tractor but many years earlier, around 1811, with the production of large and heavy machines powered by steam engines capable of assisting man in the toils of the fields. They were called “steam locomotives,” but they had little of “mobile.” Firstly, they were not self-propelled, contrary to what the term might suggest, but were pulled by horses or oxen that struggled quite a bit to move the tons of iron with which the steam engines were built and the large quantities of coal and water needed for their operation.

Set up on sturdy carts, the steam engines stood at the edge of the field and, through pulleys and belts, pulled plows or moved threshers. In an attempt to contain their mass and size over time, steam engines gave way to hot-head engines and then to petrol engines, but not before giving rise to road locomotives.

The road locomotive

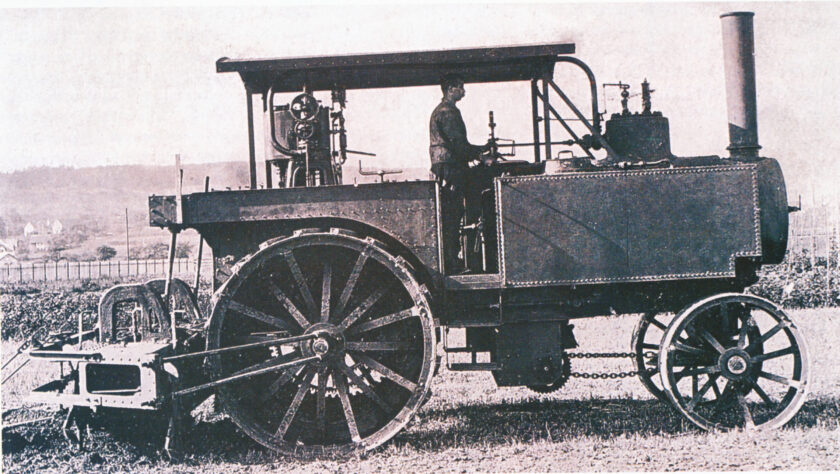

A logical evolution of steam engines was the road locomotives, which appeared around 1850 and were so named because they were self-propelled and therefore capable, albeit with difficulty, of moving from one field to another without the need for external animal or mechanical traction. They were machines always powered by a steam engine and always made on the basis of a wheeled carriage, but this could move by itself through chain or gear systems that drove large-diameter rear wheels.

The front wheels were steerable, controlled by a steering wheel located in a spartan driving position. The road locomotive performed the same tasks as the stationary steam engines and, like them, hardly entered the field due to weights and dimensions that did not allow them to move on soft terrain or maneuver at the end of a pass.

Hence the start of cable plowing, which often involved operating in pairs and placed on opposite sides of the same field. While one pulled the plow, the other was repositioned and put in a position to operate the plows in the opposite direction. Only the advent of the true tractor decreed the end of such machines in the early twentieth century, first in North America and then in Europe, but not before they were joined by other more compact and even lightweight means called “motor plows.”

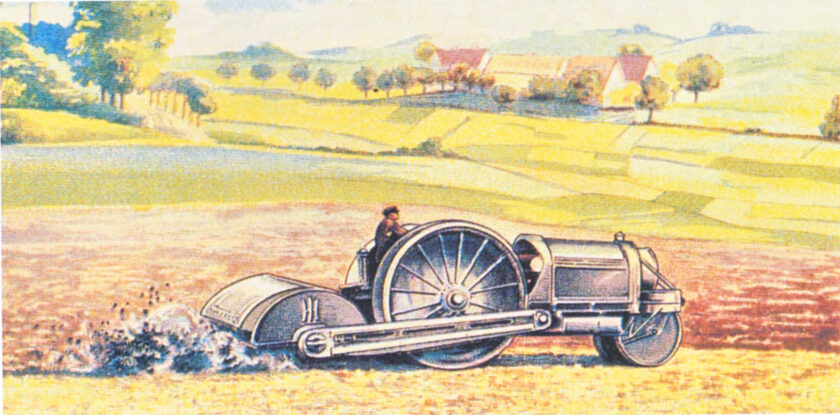

The motor plows

later.

Close to tractors, they consisted of a frame that housed one or more plows for plowing ventrally or posteriorly, giving rise to operationally finalized machines but less demanding than road locomotives. Classic examples of these machines were the Italian motor plows Pavesi and Tolotti, which appeared at the beginning of the last century.

The motor plows could be considered the forerunners of tractors, but they were still machines with limited versatility and unable to access small parcels of land or land on difficult terrain. This task was then taken up by the motor cultivators, which, precisely because of their specificity, have survived to this day.

The motor cultivators

By ideally juxtaposing steam engines with road locomotives with motor plows, one could note how the development of agricultural mechanization closely followed the evolution of agriculture, providing companies with increasingly compact machines. The latest step in this direction, towards the end of the 1920s, was the motor cultivator, a machine born to be a small single-axle motor plow driving a tiller. It was designed with advanced agriculture in mind, in confined spaces or on steep slopes, areas where tractors could not access. For this reason, the series production of motor cultivators continues to this day, despite forcing the operator to walk to follow the machine. Compared to the first models, today’s motor cultivators are much safer and easier to handle, can operate not only tillers but also a large number of other tools, and have also given rise to specialized variants such as mower-cultivators and power tillers, the latter being wheel-less and supported by a system of tines that not only work the soil but also propel the machine forward.

The salient features of the tractor

According to available documents, the first tractor was born, defined, however, as a “central mobile power unit.” It is perhaps the description that best suits a machine whose basic construction profile and operational purposes have not varied much over the decades. Today, as then, and awaiting the electric propulsion that is much talked about but less implemented, the tractor is such if powered by an internal combustion engine, which must necessarily be combined with a transmission controllable by a clutch and capable of realizing not only forward gears but also reverse ones. It must then have at least two axles, one of which is steerable and one is motorized, and must have a driving position that allows the operator to manage all functions. Thus conceived, the machine can operate as a stationary unit or as a self-propelled unit, made such by the presence of wheels or tracks. In fact, well-defined features that have been refined over the years, integrating one or more hydraulic systems into the machine and replacing pulley power take-offs with shaft power take-offs. Thus conceived, the agricultural tractor is today one of the most versatile and multifunctional machines ever built by man, provided that to be considered a true tractor, a machine must also possess one last but no less important requirement: it must have been produced in series, perhaps minimal, but in series. Otherwise, it is only a prototype, and prototypes, if they do not eventually give rise to a series, rarely make history.

Title: Agriculture before the tractor

Author: Massimo Misley

Translation with ChatGPT